In software projects, we have a tendency to repeat the same mistakes over and over again.

Stakeholders ask for estimates. Usually something along the lines of “we don’t know what we want. When can you have it done and how much will it cost?”.

Sometimes we manage to extract some requirements before we answer, but often we just resolve ourselves to providing an estimate — based on absolutely nothing.

We have that nagging feeling that we’re doing something terribly wrong. We had that bad feeling on our last project, and our estimates ended up being wrong.

But we tell ourselves:

“this time, it’ll be different”.

So we foolishly give our estimates.

And the estimates end up being wrong. Again.

Somehow we manage to get through the project. We cut corners (“we can just take out that buffer”, or “we don’t need QA, right?”). We apologize for being late. But we get through it (most of the time).

After a well-deserved break (a.k.a. a weekend off), your stakeholders ask for another estimate.

And we tell ourselves:

“This time, it’ll be different”.

Why do we repeat these mistakes over and over again?

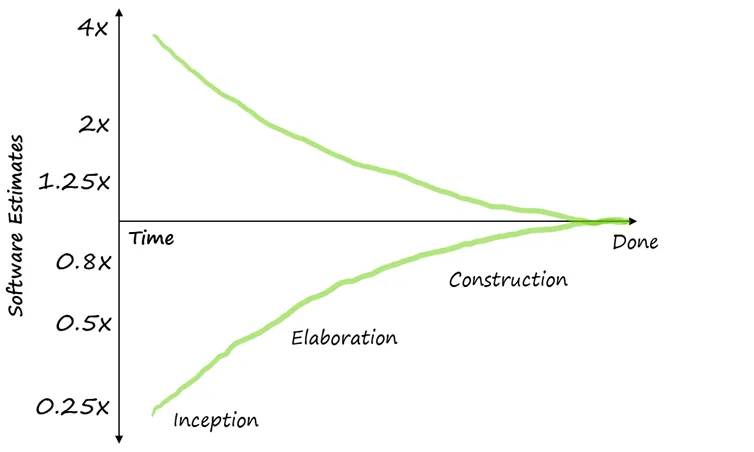

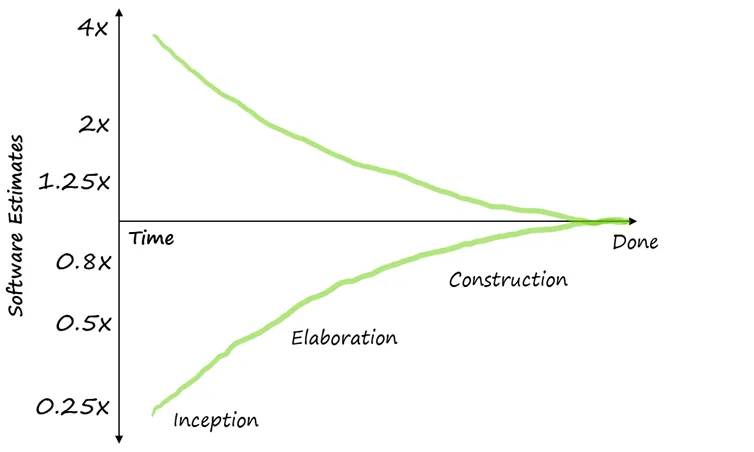

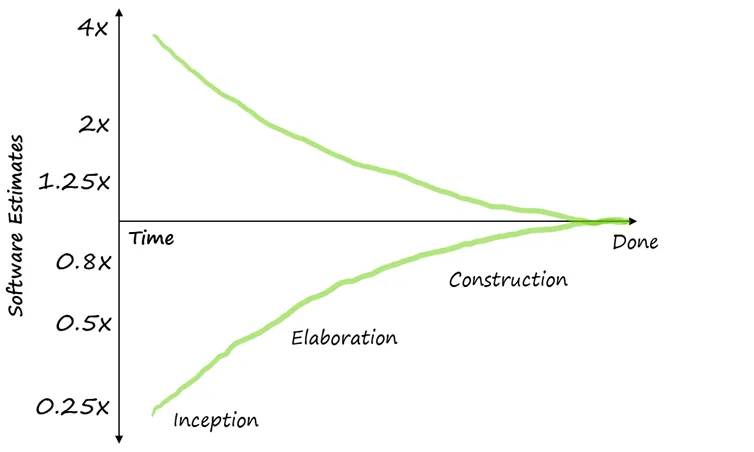

At the beginning of a software project, we know almost nothing about the product or work results, and so estimates are subject to large uncertainty.

As we do more research, we learn more information and the uncertainty decreases. Our estimates become more accurate.

When we start writing code, that uncertainty decreases even more. The more features we complete, the more that uncertainty decreases.

Eventually, the uncertainty reaches 0% — when all risks have been mitigated.

This usually happens by the end of the project (when we no longer need an estimate)

This is a concept that Steve McConnell described as the “Cone of Uncertainty” in his book Software Project Survival Guide (McConnell 1997).

Software teams regularly sabotage their own projects by making commitments too early in the project cycle. An estimate at the project Inception stage is possibly wrong by a factor of 2 to 4 times. They invariably undermine predictability, increase risks, and reduce the chances that the project will be successful.

By the Elaboration stage, the estimates can already be twice as accurate as they were in the Inception phase. They can still be off by a factor of 2, but they are suitable.

An effective team will delay their estimates until they have done enough work to force the Cone of Uncertainty to narrow.

Unfortunately, stakeholders typically don’t want to wait to get their estimates. They want to find out how much budget they should allocate (or to know how much they’ll get for their budget).

Let’s try an experiment, shall we?

Take a look at the two squares below. Without using any tools, estimate how big, in pixels, each square is.

Don’t cheat. Don’t use your browser tools or any rulers. Just try to estimate, with all your knowledge and skills, how many pixels each square is.

Pretty difficult, right?

A lot of things affect your ability to answer accurately. The blurry lines and the imperfect squares make it pretty hard to determine where your measurements should start and end.

Let’s try again with cleaner, well-defined squares:

Still difficult to guess their exact dimensions in pixels, right?

Unless you’re a cyborg or a robot (in which case I salute our robot overlords), you do not have the ability to detect the square dimensions accurately.

Now let’s try again with the fuzzy squares, but this time answer the following question: how much bigger is square B compared to square A?

You probably guessed that square B is twice as big as square A (or 4x as big if you’re comparing areas.)

.

.

See what happened? Even if the squares were fuzzy (i.e.: requirements not clearly defined), and even if you didn’t have measuring tools, you were able to guess their relative size to each other.

That’s one of the key concepts to agile estimation: as humans, we’re really bad at estimating absolute sizes, but we’re naturally good at estimating relative sizes.

As humans, we’re really bad at estimating absolute sizes, but we’re naturally good at estimating relative sizes.

By breaking your work into smaller units of deliverable functionality, and delivering that functionality in small iterations (1 to 2 weeks), you can establish a baseline for your estimates.

Start by estimating the relative size (something that is often described as Story Points) of some the product backlog item that you will deliver in your first sprints.

For example, you and your team may estimate that product backlog item B is twice as big as product backlog item A.

You can assign relative values of 1 story point to item A, and 2 story points to item B.

Deliver as many items within your first sprint as you can using a normal pace of work.

At the end of the sprint, add how many story points you delivered for all the product backlog items that got completed within the sprint.

Let’s say that you delivered the following product backlog items (PBI):

| PBI # | Estimate (Story Points) |

|---|---|

| A | 1 |

| B | 2 |

| C | 2 |

| D | 3 |

| E | 2 |

| Total | 10 |

If your sprint was 2 weeks long (10 working days), you can estimate that your velocity is 1 story point per day.

As you plan your second sprint, you can base your estimates by comparing the story point estimates for the work that you already did against the product backlog items you’ll be delivering during this next sprint.

For example, let’s pretend that you delivered a total of 8 story points in the second sprint:

| PBI # | Estimate (Story Points) |

|---|---|

| F | 1 |

| G | 1 |

| H | 2 |

| I | 2 |

| J | 2 |

| Total | 8 |

Your sprint velocity for sprint #2 was 0.8 story points per day. Your average velocity is 0.9 (or 10+8 / 20) story points per day.

On your third sprint, you repeat again. This time, let’s pretend you managed to deliver 12 story points (what can I say, your team is good!). Your average velocity is back to 1 story point per day (10+8+12/30).

As you do more sprints, your average sprint velocity average will become more and more accurate. Your estimates will also become more accurate.

Best of all, given your velocity average, you can start estimating how much longer it will take to deliver the rest of the product backlog items (as long as you have story point estimates for your backlog).

As we established earlier: even if the requirements are fuzzy (like those squares), you can still get a pretty good idea of the relative size estimates. As your requirements become clearer (for example, when you clarify the product backlog item prior to sprint planning), your estimates become more accurate.

Stop treating software estimates as a precise prediction of a project’s outcome. It isn’t.

The best scenario would be to fund enough of the project to establish a baseline (or velocity) so that your future estimates can be more accurate (because you can compare your remaining Product Backlog Items against the work you’ve already done and build relative estimates.

Best thing to do is be honest. Tell them that you don’t know how long it will take. Tell them that your estimate is your best guess, but that at this time it can be off by as much as 4 times. Ask them to give you enough time to complete 2 or 3 sprints, after which time you’ll be able to provide them with a more accurate estimate.

Do yourself (and everyone else in IT) a favor: stop treating your estimates as a precise calculation and start having a “Cone of Uncertainty” conversation. In my experience, most stakeholders are smart enough to understand that your estimates will become more accurate as the project evolves.

As Steve McConnell says:

The primary purpose of software estimation is not to predict a project’s outcome; it is to determine whether a project’s targets are realistic enough to allow the project to be controlled to meet them.

—Steve McConnell, Software Estimation: Demystifying the Black Art

The Cone of Uncertainty, Construx Software.